Behind the Scenes: My Favourite Sketches of 2024 — Part 1

Some of my best sketches from last year — and the stories behind them.

At one sketch a week, I slowly make progress with 52 sketches a year. At times—holidays, busy periods with other jobs—it seems like a lot. Other times, I reflect that it's far too slow. So many ideas to cover, and I'm snailing my way through.

If you joined recently, or just dip into a sketch now and then, I thought it might be fun — now that the dust has well and truly settled on 2024 — to pick out a few personal highlights from last year.

These are sketches that:

seemed to resonate most with readers

have particular meaning for me

I'm proud of

I keep coming back to and resharing or referencing

I've added some commentary to each—things like where it came from, why I like it, where the sketch is based, how I landed on this visual, and what's happened to it since.

Perhaps it will remind you of a few you enjoyed, or introduce you to some you missed. As always, I've linked to the full sketches if you'd like to dive deeper.

This kind of behind-the-scenes post is for paid subscribers — but the weekly sketches stay free as always.

Here are 5 of my 15 favourites from last year's 52. This time, I dig into: the Fundamental Attribution Error, the XY Problem, Normalisation of Deviance, Rivers and Buckets, and Muddy Puddles Leaky Ceilings.

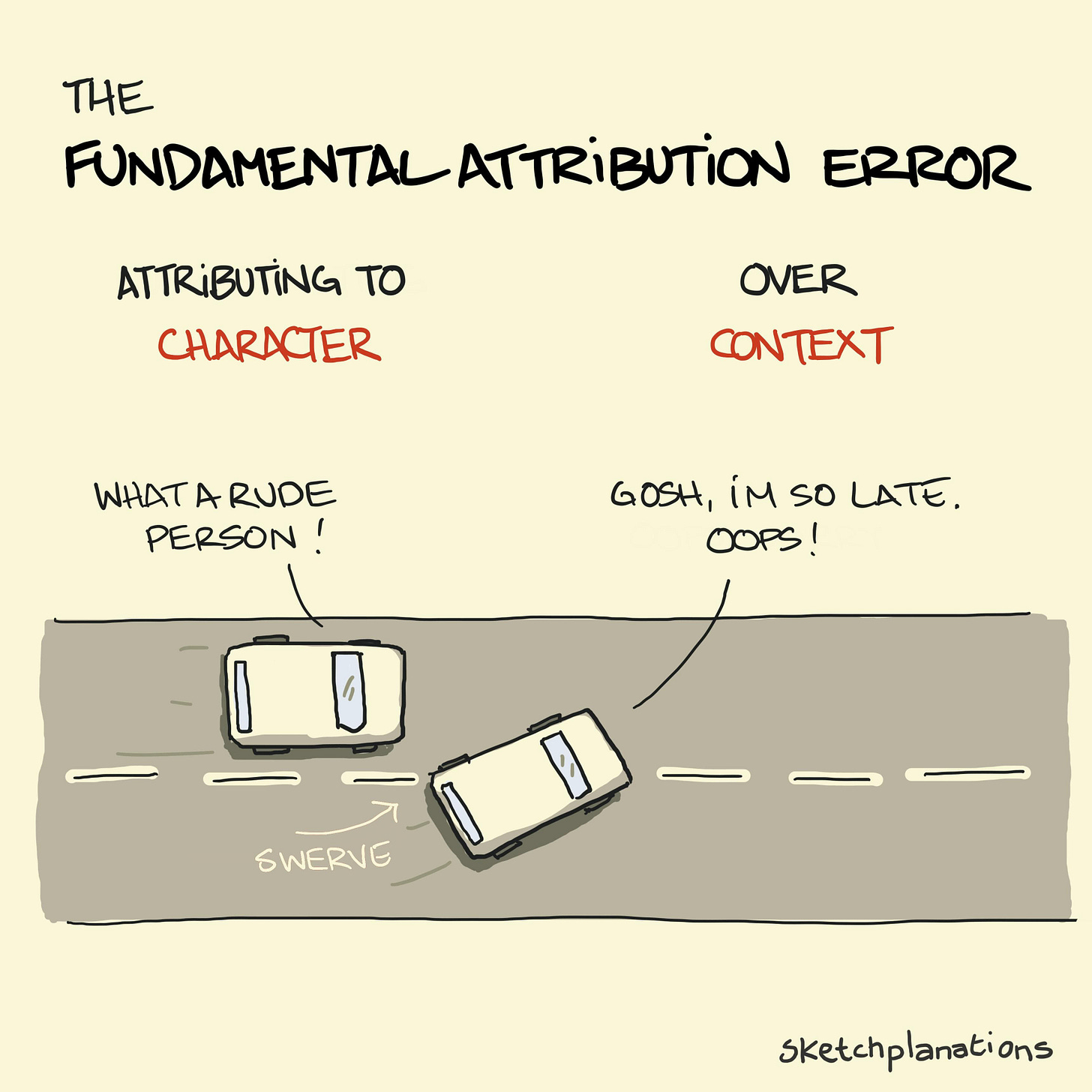

1. The Fundamental Attribution Error

The fundamental attribution error is one I think of so often. I learned about it while working at Jump Associates (I think). For me, it's one of the foundations of a People Make Sense philosophy that helped me with social research and understanding why people do what they do.

Few people are acting outright evil-ly. Most people take actions that make sense to them in their context. As a thought experiment, if you were to ask someone who appeared inconsiderate if they thought they were inconsiderate, usually I think they'd give a different perspective.

From the outside, however, many of us are quick to judge the person rather than the situation. A classic situation is driving. It works so well because in a car, we only see the behaviour of the other cars and not the people inside, and it makes us quicker to judge.

Philip Zimbardo, of the Stanford Prison Experiment fame, gave a talk on the psychology of evil, where he suggested it was less about 'rooting out bad apples' in an organisation. What's more likely is that a bad barrel is causing them to go rotten. The apples themselves are fine, but our behaviour depends on context.

We touched on the fundamental attribution error in the podcast episode about Hanlon's Razor, which I loved. It's also related to two other sketches I've covered: attribution bias, and self-serving bias.

I have another sketch related to Philip's work, which I really like: Be real on the internets—I'm glad to see that since sketching this, it feels like we've come a long way on it.

Keeping in mind the fundamental attribution error helps me empathise with others and remember that I don't know their circumstances. (A little like this excellent Liz and Mollie visual from

)Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sketchplanations to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.